Dealing with uncertainty

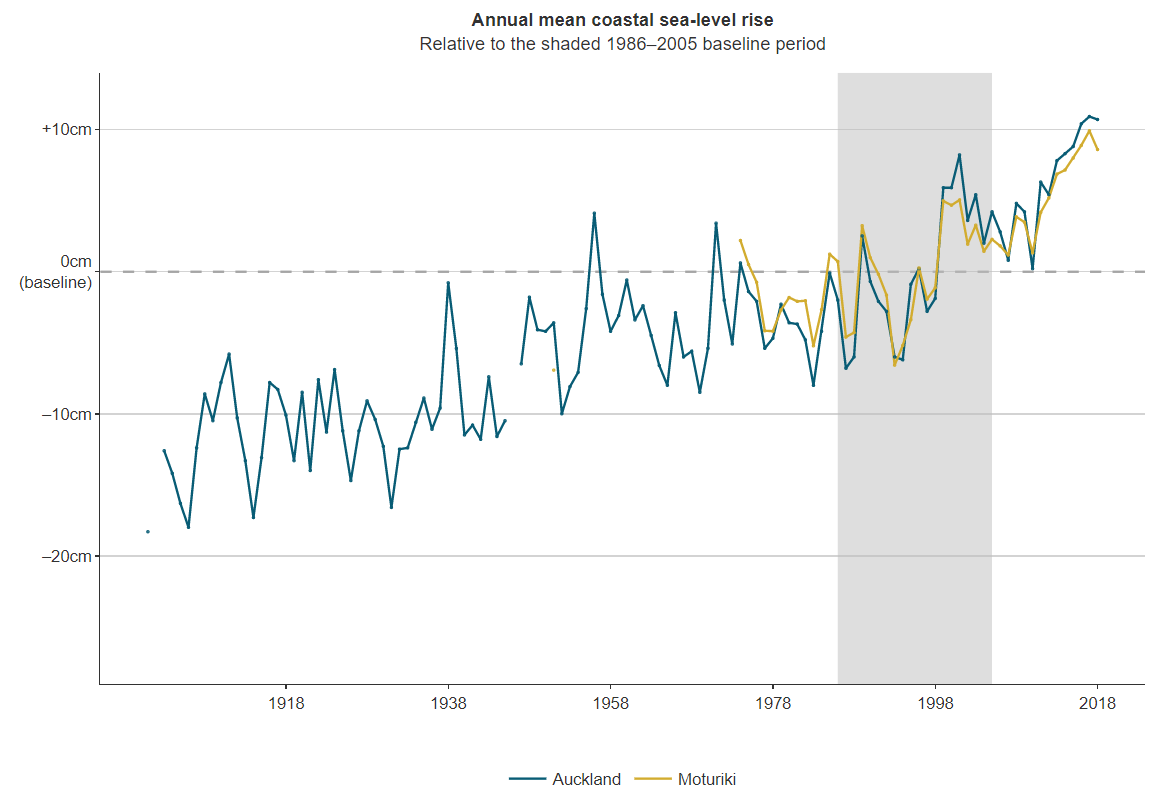

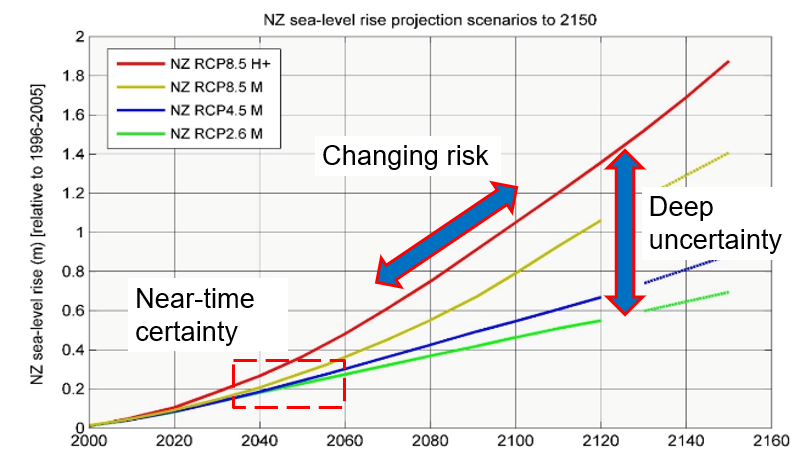

There is uncertainty associated with the predicted effects of climate change. Considering sea level rise (SLR), there is a high degree of near time certainty (see top figure below) and close alignment of the different modelled SLR scenarios[1]. However, as time progresses uncertainty increases as the different modelled scenarios diverge; illustrated in the bottom figure below (NZ-wide SLR projection).

The MfE 2017 guidance recommends that the three RCP median (M) SLR projection scenarios (RCP2.6 M, 4.5 M and 8.5 M), plus an upper-range scenario (RCP 8.5 H+), should be used in adaptation planning assessments[2]. The Thames-Coromandel coastal adaptation project adopted this approach.

Uncertainty also exists with respect to changes in storminess (frequency and intensity) (see "CIH methodology"), changes in sediment transport processes, vertical land movement (see "Coastal Environment Baseline Report" and https://www/searise.nz/), and the effectiveness of intervention options, for example.

It is for this reason that the signals and triggers included in the pathways for an adaptation measure to be taken (such as ‘protect’ or ‘retreat’, see "What can we do about it?") are not theoretical or based on modelled outputs. That is, they are to be based on real measured or experienced change, such as the increasing frequency of storm events, 0.2m of SLR or loss of 80% of the foredune or the withdrawal of insurance cover.

Hence – no action will be taken unless and until monitoring data indicates that a trigger has been met. Therefore, establishing a comprehensive monitoring programme is an important next step (see "Next Steps").

Footnotes

- 1 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change. It prepares comprehensive reports about the state of scientific, technical and socio-economic knowledge on climate change, its impacts and future risks, as well as options for reducing the rate at which climate change is taking place. It has modelled predicted SLR based on different emissions (representative concentration pathway – RCP) scenarios.

- 2 Although it acknowledges that it will be challenging to achieve the RCP2.6 M scenario, because of the rapid and large reductions in emissions required globally.